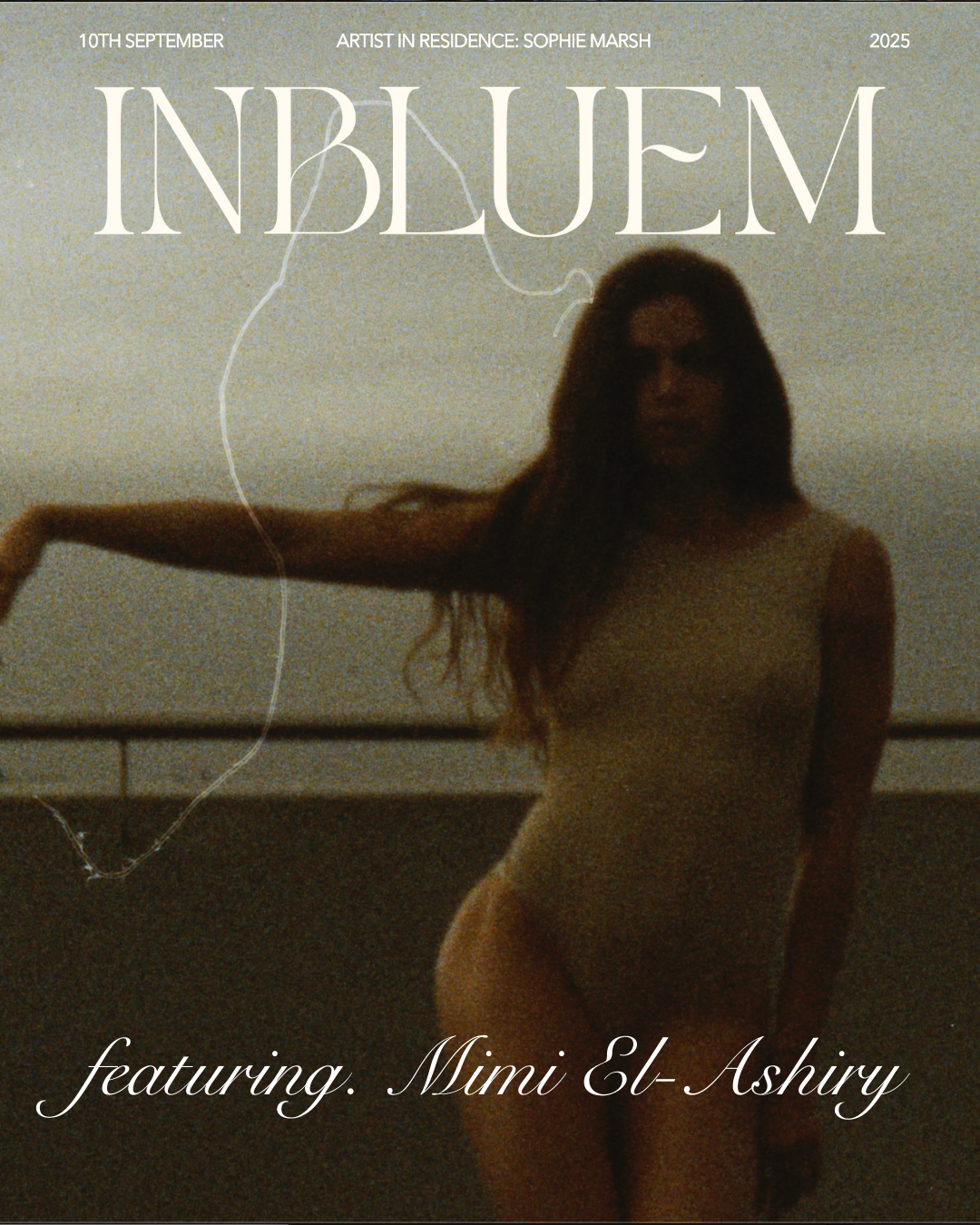

Mimi El Ashiry in Conversation: The Radical Act of Inhabiting the Body

Mimi El Ashiry has lived her entire life near the gaze of the lens, and for over the last decade, within the panopticon of digital consumption. As a child model, then dancer, then muse of the Tumblr era, she matured in a world in which her essence was frequently extracted and often transfigured into surface for consumption.

The paradox and lesser understood relic of Mimi's youth is that her body was both her gift and her battleground, something she had agency over but usually in service of someone else's vision. What was programmed concurrently from an industry obsessed with symmetry and slenderness was a dissonance where a body was seen as currency (for praise, for money, for perception) but rarely honoured as vessel. Yet her journey throughout her twenties, attributed by El Ashiry as being purely intuitive, allowed this friction to lay the seed of transformation. Returning to dance, yoga and free improvisation as an "ex"-dancer, reclaiming her dancer title in new light, her body has become the site of excavation, the place where she reclaims essence again and again.

With her thirtieth birthday in sight, Mimi and I exchange conversation on the phone, the presence and intelligence of her voice luminous with a quality of groundedness that suggests someone who is well adept at making peace with inhabiting her wholeness. She acknowledged that this journey had been a long one, and that the foothold of her thirties presented a new changing landscape in itself. When I ask how she experiences beauty now versus her earliest industry days, she pauses, considering.

"I've been modeling since I was crawling, so it's not about when I came into the industry but how I perceived beauty through my surroundings growing up," she begins. "There was definitely a right way to present yourself. As a young girl, you can misconstrue this idea of presenting yourself well as needing to be perfect."

What emerges in our conversation is a portrait of the particular psychological architecture built by industries that profit from female form. El Ashiry describes a "quiet competitiveness" that could go undetected to an onlooker, always measuring herself against an impossible standard.

"For years I quietly competed, always seeing myself as less-than. That comparison led to body dysmorphia, eating disorders, and a constant sense of inadequacy," she reflects. "I would always see other people as more or bigger or better or more beautiful and would just quietly try to tell myself I was better. But looking at the big picture, it feels like an overarching theme of just never being enough."

This quiet violence, of the internalised critic whispering inadequacy while the external world rewards appearance, reveals something crucial about how beauty functions as social control. El Ashiry's experience mirrors countless women who grow up understanding their bodies as sites of judgment, up for interpretation and renegotiation, rather than sources of wisdom.

The transformation hastened unexpectedly several years ago, when old patterns of self-criticism resurfaced, El Ashiry found herself afraid of sliding back into familiar territories of dysmorphia and disordered eating. Instead of seeking external solutions, she created what she calls "an uninterrupted place" for movement and music.

"I intuitively locked myself in a room, lit some candles and incense, did some breathing, and ended up moving my body around, trying to coach myself through it," she explains. "This vision came to me of this version of myself that was wild and strong and fit and curved with beautiful strong muscles."

The vision she describes feels almost totemic as a reclamation of her body's natural strength and fortitude that had been trained out of her in pursuit of the thin ideal. "My natural body is muscular. I don't have very long bones and thin muscles; they're quite muscular. Seeing that in the vision gave me the perspective that this was my healthy place, my power and strength."

This moment of internal revelation stands in stark contrast to beauty culture's emphasis on external validation. When I ask where beauty lives in her body now, she closes her eyes briefly, accessing something visceral.

"She feels wild and grounded and very nourished," she says. "She feels like she lives in a mixture of womb and belly. I feel this is symbolic of the importance of nourishment for our creativity in the womb space, but also nourishment in our stomachs, fueling ourselves with nourishing food so that we're strong and healthy. That exudes a natural beauty."

The language she uses—"she," as if speaking of an aspect of herself that exists beyond the constructed self—suggests a relationship to beauty that transcends individual aesthetics. As life force, as presence, as the particular radiance that emerges when someone is fully inhabiting their own experience.

This understanding has shaped her work facilitating movement workshops through her practice, Move and Manifest. What she witnesses repeatedly is how disconnection from authentic expression creates a particular kind of suffering, especially among former dancers who believe they've "lost" their dancer identity.

"The thing I hope people realise is that the more they lean into their unique way of moving, not a way that is correct or cute or cool or sexy, the more beautiful it is," she explains. "When someone is embodied in their own expression, present with the sensations they're feeling in their body, you can't take your eyes off them."

This observation cuts to something essential about beauty's relationship to presence. Anyone can learn technical perfection, she argues, but the quality that draws attention is someone moving from "this visceral place of feeling and presence with the sensation in their body."

"The less you want to try to make it beautiful, the more beautiful it will be," she says, a paradox that speaks to beauty's resistance to manipulation.

The conversation turns to contemporary beauty culture, and El Ashiry's expression grows more serious. She speaks of feeling "slightly concerned" about the artificial beauty standards proliferating across social media of faces that "look like AI basically."

"It worries me that young girls could be exposed to the crazy and no longer subtle changes happening to people's faces and bodies," she says. "I experienced body dysmorphia just from seeing pictures of girls who were thin, who didn't have work done to their faces. Now it's not just about weight, it's so much more altering and irreversible."

Her concern extends beyond individual choices to cultural amnesia, the risk of losing touch with what unmodified faces actually look like. "Sometimes when I look in the mirror, I'm like, 'Oh, that's right. This is what a normal face looks like,' because we get so used to such exaggerated features."

The conversation shifts when I ask about her Egyptian heritage, and something in her demeanor expands. She describes learning Arabic and being struck by the everyday poetry embedded in common phrases as a cultural inheritance.

"A way to say good morning is 'sabah al-full' or 'sabah al-noor' meaning morning of jasmine or morning of light," she explains. "You're telling people the morning is full of jasmine or the morning is full of light. That's just your typical good morning, it’s so beautiful."

In her own home-coming to Egyptian culture she expresses the presence of an almost infinite source of beauty she is discovering in her ancestral language.

"The funny thing is, that language we read in Khalil Gibran's poems as being so symbolic and beautiful—some of the typical daily phrases are like that. It's normal to speak that kind of beauty into the mundane."

When I ask about the paradox of sharing vulnerability from a position of conventional beauty and privilege, El Ashiry's response reveals the particular burden of visibility. "There's a part of me that judges the part of me that wants to share my experience because I know I've had so much opportunity. I have beautiful hair and skin and a healthy body. My inner critic wants to stop me from sharing how I've really felt."

The tension between external perception and internal experience illuminates something crucial about how beauty functions as both gift and burden. The assumption that conventional attractiveness excludes authentic struggle reveals how thoroughly we've internalised beauty as hierarchy rather than diversity of expression. Across beauty standards, this fear of not being valid in our experiences speaks to a deeper silencing of humanness we are all privy to.

"I actually feel more surprised when people resonate and I don't get criticised for being authentic," she admits. "There's a part of me that feels like I'm going to get criticised for sharing my experience."

As our conversation draws to a close, I ask about legacy. El Ashiry's response reveals someone who has moved beyond the performance of impact toward something more intimate.

"I honestly haven't thought about leaving my mark or legacy behind," she says. "I think I'm in the process of thinking about what are my gifts and how can I share them in a small way with the people around me. How can I be present? How can I enjoy this temporary life more?"

There is a felt relief in her shift from grandiose ambition to present-moment attention that exactly mirrors a desire to know embodied presence.

"I spent a lot of my twenties thinking I'm going to be a famous actress, I'm going to be this, I'm going to be that, all very big with pressure to leave a big mark. At this point in my life, I've taken a step back from that pressure and am considering how I can make a difference on a micro level right now."

We touch one last time on Mimi’s 2026 Move and Manifest trip to Egypt, as despite Western fear-mongering of the region, it stands to be a safe container of the commitment to getting outside of the comfort zone and the action-making that Move and Manifest inherently is.

"I often get asked about gods and goddesses in ancient Egypt, and although I love visiting the sites, there's so much beautiful history and gorgeous symbolism that I appreciate," she explains. "But what I've come to connect with in recent years is actually the beauty of the current culture and the beauty in what people who have only looked at ancient Egypt might see as mundane."

Her voice becomes noticeably more animated: "The rawness of the country, all the different people, there's Egyptians and Nubians who come from Sudan that are actual descendants of ancient Egyptians. There's the Mediterranean coast and deserts and the Red Sea and coral and free diving and beautiful food. The people are so warm, the Islamic culture is beautiful, the language is gorgeous, the architecture is stunning."

This shift from mythologised ancient Egypt to lived contemporary culture reflects the same movement she's made from idealised images of self to embodied reality. "I've stopped concerning myself with the big wormhole of symbology in ancient Egypt, which I think is more outwardly beautiful from the outside," she says. "When I've spent time in Egypt and Cairo, I've realised the real beauty lies in the current culture and understanding what it's like as a human being now to live there, not what the pharaohs were doing."

Mimi’s journey offers no simple solutions to beauty culture's complexities. Instead, it begs us to return to the body as a source of wisdom, away from performance. In a world increasingly dominated by digital manipulation and artificial enhancement, she points towards beauty as archaeology rather than architecture. As the devout uncovering of what lives and breathes in the present moment. In the radical act of inhabiting, fully and fiercely, the life we're actually living.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.